Berlin

13

Pan Daijing

Jessika Khazrik

Johanna Hedva

Jessika Khazrik: In one of his treatises on music, the 9th c. Iraqi polymath Al-Kindi, who was at once a mathematician, cryptographer, astrologer, physician, musician, and philosopher, divides melodies into three exhaustive genres: At-Tarabī, Al-‘aqdāmī, and Ash-shajawī. At-Tarabī is suitable for relish, enjoyment, and what he describes as “at-tanaghom”—falling into a melody in a soft hum, so to speak. Al-‘aqdāmī advances boldness, resolution, salvation, and misery, while ash-shajawī is congruous with processes of grieving, mourning, and rest. He takes his argument a step forward by stating that every genre has its own time of the day: mid-day, night, and the beginning of sleep, respectively. In your music, one senses a great sense of grief that is, at once, full of “tanaghom” and a cathartic salvation that fills the space but remains impossible. What do you think of Al-Kindi’s claim?

Johanna Hedva: Wow, I love that. I don’t know Al-Kindi—what a gift you’re giving me! I just ordered a bunch of his books.

His three genres corresponding to different emotions and affects as well as times and cycles of the day sounds right to me; although I’m unfamiliar with his full thought, intuitively that makes a lot of sense. In the astrology I’ve studied and that I practice with clients, which is informed primarily by the Hellenistic (Ancient Greek and Roman) tradition, which of course, colonized its knowledge from earlier civilizations, including Ancient Arabic, there is a great emphasis on different times of day instigating different kinds of selves and, so, fates. For instance, if you are born at night, you are of the nocturnal sect, which means not only that your Moon sign is stronger than your Sun, but that the planets treat you differently (Saturn is harder on you, Mars is easier; if you’re born during the day, or in the diurnal sect, it’s inverted). We are different people at night than we are during the day. At night, we need sleep, rest, care, vice; we exist in dreams, somewhere so profoundly mysterious and gone from this world, but also mundane and familiar. During the day, we are an ego, a will, building a telos, summoning agency. Activities belong to certain times too. Witches, of course, do their spellcraft at night; where as the time of commerce and production is during the day.

I’m born at night, and my Moon is dignified in the sign of Cancer, so when I read your question, I immediately felt pulled toward the night genres: al-aqdami (I love that boldness, salvation, and misery are under the same umbrella), and especially ash-shajawī.

The piece I’ve been touring this year, and that I worked on with Pan in this residency, would fall into the ash-shajawī category. It’s called Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House, and is a ritual of grieving that I made for my mother, who died last year. It’s title comes from an astrological signature that I have in my natal chart that binds me to my mother; I am as bound to her in death as in life. To make Black Moon, I studied different musical traditions of lament and grieving songs, particularly the vocal traditions. In Korea (my father’s Korean), there’s a kind of singing called P’ansori, which demands the voice of the singer become as ravaged as possible. The more ancient and weathered and shredded the voice sounds, according to P’ansori, the more beautiful. To train, P’ansori singers stand next to waterfalls and try to be as loud as the crashing water. When I first learned of P’ansori, it felt huge with sorrow, and I was totally kidnapped by the need to do it, to sing this way. Singing my grief felt like it needed to ravage my voice, that that was an accurate representation. On the other hand, my mother’s ancestry is Irish, Czech, and German, and the vocal traditions of lament from those places have almost an opposite aesthetic from P’ansori. They are keening traditions, so the voice is like a bell sounding through the darkness, clear and crystalline and resonant. I came to understand that grief produces different sounds, and so I tried to make my voice a house for all the different kinds: from growls and guttural roars to high, choral wails.

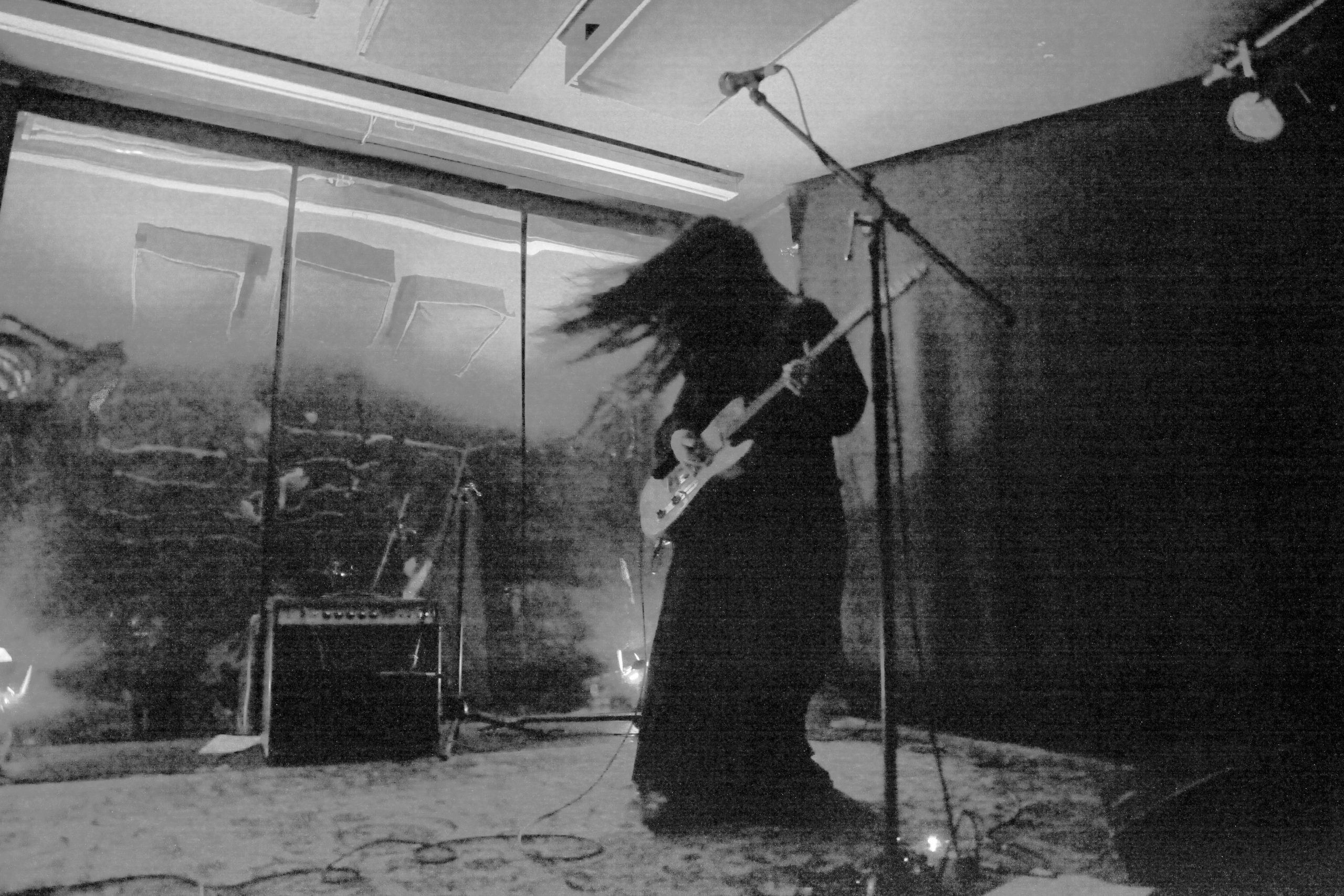

Black Moon is a solo performance of voice and guitar, so the guitar is a voice too, it’s like a duet. I spent a lot of time customizing my guitar so that it could be a perfect partner in this piece. As a voice, it needed to have a huge range, to sound like a hag, at times, and at others, like a bell. It also needed to be able to make the sounds I can’t, but it pushed me to try to make them too. One song, for instance, has a high F note on the guitar, and I really wanted to hit that with my own voice too, so we could swirl around each other up there. Thanks to my vocal teacher, I finally managed to get up that high.

I’ve always thought of Black Moon as a passage through time: it has a beginning, middle, and end. At the beginning, I embody Death as a being that has arrived, saying, “Your time has come.” The first song is a doom metal song; it should feel violent, terrifying, the feeling of death panic, that huge instinctive refusal, no, I do not want to die. In the middle, I am me as a grieving child, trying to come to terms with the unbearable, that my mother is gone forever. There is a crooning pop ballad here, and a song that Pan said reminded her of a lone cowgirl on a horse in the vast desert. But by the end, I embody my mother, specifically her soul as its preparing to go to the underworld. She keeps saying she needs two coins to give to the ferry man, and the finale of the piece is a reciting of the Hail Mary prayer through a wall of drone noise. I sing this a cappella, a single voice against the abyss, and then the vacuum eats abyss.

So, yes, as you say, “a cathartic salvation that fills the space but remains impossible.”

JH: when i read your astrology chart, i was pulled toward your five planets in scorpio in the 11th house, the house of sociality and belonging. about this signature, you told me about your concept of the “anti-war war.” can you talk more about this?

Ayy, where to start : ) ? I don’t usually call it “anti-war war” or “a war”. This double negation came out of my mouth when you, blown by the number of war/insurrection/strategy-related goddesses and gods in my chart, kept on repeating the word “war”.

I am constantly affected by military production, and to be honest, there is nothing good about it. It is an obstacle that reproduces obstacles and safeguards classist structures that risk many futures. There is also nothing singular about being constantly affected by militarization as these embattlements are the main relational frameworks that capitalism and the nation-state model collectively throw us in. However, their influences becomes more or less visible, encrypted and normalised depending on where in the world you are, and how you position yourself in relation to history, the future, and belonging. These influences are very visible and detrimental for me. They sound through in my childhood; my relationship with the cities and environments I come from and circulate in (computation, universities and the internet, etc.. included); my relationship to any notion of future, ecological care and progress, as well as my work around techno-politics and counter-surveillance and my practice in electronic music and vocoding.

While militaries exist to guard the specificities of a territory or state, they are all the same for me. The only military coup that can ever exist is a de-militarisation that would de-classify a military personnel into a civilian and by so doing, undo this binary system/occupation. In military philosophy, or what my last university used to call “military science”, laughs, knowledge is proprietary, classified, and emulating. Yet, it always attempts to perform “an opening” and a “surprise”. When I was doing my postgrad studies in the US, I audited several classes with the US Army. From afar, it looked so hilarious as I was the only non-military personnel. In a room filled with super brawny men in full camouflage, I immediately stood out with my blue curly hair, dark skin and iridescent clothes. From the inside, it also seemed so brutally hilarious and ludicrous. For example, in the “Fundamentals to Military Science” class, when learning about a new offence or defence strategy, we were made to watch 50-110 sec. clips from epic Hollywood films such as “300” and “Kingdom of Heaven”, usually played over 10 times… The military-industrial-academic-entertainment complex playing it right in your face, heheh.

If we look around us today, the world is becoming increasingly uninhabitable. In many places in the world, people are concurrently revolting against the draconian economic models states perpetuate. Everywhere, who is, and has always been, very violently retaliating against our revolutions? There have been very serious anti-militarist struggles and political theory not only during the anti-colonial and anti-imperial wars, but also all throughout the 19th c. and the first half of the 20th. Anti-miltarism was very strong and pronounced, especially in Germany, before WWI, and between WWI and WWII. Take for instance, the writings and activism of Clara Zetkin, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxembourg. Many similar strains of anti-militarist thought can be found today on the streets of Baghdad and in fields like feminist philosophy of science. I’m all for letting it pervade into everything. Everything.

On another hand, I enjoy so much being in a crowd. This meek, mysterious and opaque feeling of dis-identified belonging or anonymous solidarity that one experiences in a crowd, in a protest or in a club or online, is very dear to me. It’s one of the main reasons why I make electronic music.

JK: Now returning to your answer. It was so wonderful to read you write about the inception and and quiddity of “Black Moon” before watching it in full. I’ve been wanting to ask you a question I often ask myself. Can music avenge for what literature fails to collectively create? Speaking together now, it does seem that this question deserves a conversation of its own, so I will try to keep it simple. Beyond the thematic, how do you feel your practice as a musician and as a writer inform one another? How does your process in writing and composing converge/diverge?

JH: I like to say that all of my work—no matter if it’s a novel or an album or a guitar solo or screaming in a room or dragging a hand through water—is writing. For me, the definition of writing is simply that it’s language embodied. But I like to explode the concept of bodies at all, of what a body can be. I like to work in a way that proposes a body can be anything, even something—or, especially something—that doesn’t have material form. So, writing is what creates a body but writing is also what unmakes a body, writing is a body itself and writing is an entity that undoes my own body.

The biggest difference between writing and making or playing music—and this will feel basic and obvious, but I think it’s actually pretty profound—is that when I write, it’s silent, and when I music, there’s sound. I write as soon as I wake up; I write in order to wake up. Coming out of sleep is long for me, like hours long, trying to get from there to here, and I feel dazed and inchoate, my brain furred, and if I speak at all, or make any noise, or read or hear anything from anyone else, it cuts sharp and harsh, and it ruins my ability to write. So I go to the desk before I do anything else, and I sit there, in silence, working word for word, pulling each word from the nothing onto the page, until I have 500 words. I do this every day. I let it take as long as it needs, so sometimes it takes 20 minutes, sometimes three hours.

With music, it’s also a kind of waking up, but a waking up with and into sound. It’s like inviting in a force that will reverberate through everything, and, since the kind of music I play is very loud, I have to go to a special room so I won’t bother anyone. (Just writing that, I realized how both writing and music-making are so solitary, at least for me.) I feel radically transformed by sound, turning my amp all the way up, screaming until my whole body is irradiated with my voice. As much as writing is about what a body can be without material form, music and sound always instantiate materiality, that is, they make matter. Sound, though its immaterial as a thing itself, needs matter to exist, to ripple through, to resound off of. When I sing, for example, I can feel it in my skull, changing my bones. I need to inhale air from the outside and take it into myself and inside my lungs it is changed. Playing the guitar is like holding a body in your hands; it’s an encounter between two independent bodies.

I know it must be different—writing words versus composing music—but I’m not sure if I can articulate it, other than to say both are a kind of alchemy. They both deal with what we cannot see, with what is immaterial, and what we can see and hear and feel, with what is material, and the point of encounter between these two is where I want to live.

JH: in the studio, i’ve seen that you use many, many electronic instruments to make your music, and we’ve had some great conversations about our critical relationships to technology. can you explain your philosophy of technology, and how you use tech in your work?

For me, technology is very dynamic. I’m dynamic too. Ultimately, I would like tech to support my work as much as I would like to support its own development. Technological advancements are not only performed through writing new updates, but also through re-questioning our ontological and economic, techno-political relations.

My machines feel more like a miniatured space, a micro-world, rather than a body, though I can greatly relate to the intimacy you insinuate through your guitar. Every machine has its relatively similar or distinct set of protocols and relational frameworks that one can visit with new inputs, re-link and/or defy with ad infinitum possibilities. However, I would like to participate in making changes on the protocol level. Since technology has become so complex today, in ways that might often demand us to conduct investigations that surpass the question of use, to be more technologically-mediated is to also deal with reams of desire and different levels of illegibility and presence.

It is very hard to speak in any general sense when thinking about technology. For instance, training a neural network with your voice is very different than playing a haptic drum pad or a drum machine with the output of that neural net or reproducing SIGSALY with code. Vocoding and vocal encryption – allowing a machine to ‘change’ your voice or hide the content of your speech, make these relations much more dramatic. I try to keep these playful techno-relations of freedom, command, collaboration and control visible when I perform.

JK: I very clearly feel a strong time dilation in your music. This time dilation made much more sense when you shared with me your trenchant, experiential review of watching Sunn O))). From what I have seen during rehearsals, your music and your performance is, indeed, very akin to the scream that one utters before death. But here, in your music, the last blare/scream/utterance is protracted… even if it comes early. It is like leaving the body against flesh, and it, kind of, does not believe in time and space. Write to me about the metaphysics of sound and this nebulizing power that seems so familiar to you.

JH: Well, I guess my feeling is that “the scream that one utters before death” is life itself.

JH: so: magic, sorcery, witchcraft, necromancy, alchemy—i see these as some things through which you and i converge. can you speak to that?

JK: Ayy, Johanna.. these questions require a new life : )